Scheduling

One of the more powerful features of eventkit is the ability to independently control the asynchronous behavior of every observable and the execution of its side effects.

That's pretty wordy, so let's break it down:

Every observable can adopt different async behavior

What we mean by async behavior is observing the what, when, and how of an observable's execution.

// What has to happen before either of these resolves?

await mySubscription;

await myObservable.drain();Most commonly, the what that belongs to an execution is any work thats associated with it (as described in Async Processing), the when is the specific point in time in which all the relevant work associated with an execution is completed, and the how is the manner in which that work is executed.

While this seems like an obscure detail, it becomes vitally important when differentiating between types of observables. For instance:

const myObservable = AsyncObservable.from([1, 2, 3]);

await myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

console.log("done");This is an example of an observable that yields 3 values then completes. The execution path is easy to follow ⎯ we wait for the observable to yield its values, then we wait for the subscriber to finish processing them.

But what if you have an observable that yields values indefinitely?

const myObservable = AsyncObservable.from([...Array(Infinity).keys()]);

await myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

console.log("done");The 'done' log will never be reached because the observable will never complete. We might want to observe that never-ending execution a little bit differently so it's not perpetually blocking.

This is a contrived example, but for all intents and purposes a Stream is an extension of an AsyncObservable that will indefinitely yield values. In the case of a Stream, we're more interested in observing the side effects that come from pushing values to it.

const stream = new Stream<number>();

stream.subscribe(console.log);

stream.push(1);

await stream.drain();

console.log("after drain");

stream.push(2);

stream.push(3);

await stream.drain();

console.log("done");

// output:

// 1

// after drain

// 2

// 3

// doneThe implementation of Stream achieves this by using this unit of control and altering it's behavior ever so slightly (as described in Async Processing).

Every observable can control the execution of its side effects

As described in the Observable Pattern guide, an observable is a push system that decides when to send data to its consumers. This is an important capability that lets us control the execution of its work (the how). In eventkit, we do this by providing a Scheduler object to the observable that manages the execution of its side effects.

(See an example of this here)

The Scheduler object

The Scheduler object is the logical unit that coordinates all work associated with a subject. Eventkit covers most of the types of scheduling you need to do by offering a range of out-of-the-box schedulers, but the idea is that you can provide your own implementation if needed. The idea of a scheduler is pretty simple:

- You can add work to a subject by calling

add() - You can schedule work to be executed for a subject by calling

schedule() - You can ask for the status of the completion of a subject (in the form of a Promise) by calling

promise() - You can dispose of a subject by calling

dispose()

When you call:

await subscriber;

await observable.drain();you're effectively calling:

await scheduler.promise(subscriber);

await scheduler.promise(observable);And when you call:

await subscriber.cancel();

await observable.cancel();you're effectively calling:

await scheduler.dispose(subscriber);

await scheduler.dispose(observable);There's a couple of important things to note here about how schedulers work:

- All work is represented as promise-like objects, so we can assert that a subject is considered "complete" when all of those "work promises" have resolved.

- Every observable has its own scheduler object that acts as its source of truth in regards to the work associated with it.

- When

schedule()is called, that doesn't implicitly mean that the work will be added to the subject. Typically theschedule()method will calladd()internally to add the work, and orchestrate/defer/forward the work's execution if needed.

INFO

Scheduler is a class that's exported from eventkit that defines the default behavior (and is what a lot of schedulers extend), but the interface that's accepted by most objects is the SchedulerLike interface.

ScheduledAction

One way that work is represented is through the ScheduledAction class. This is the base class that represents any work that is scheduled to be executed later for a subject, namely cleanup work and subscriber callbacks.

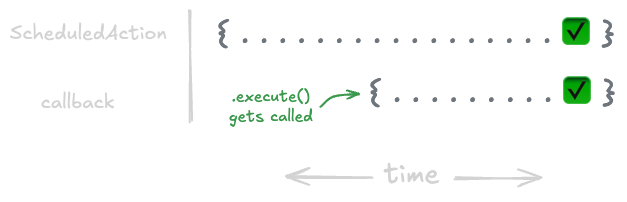

A ScheduledAction is a promise-like object with a two-phase lifecycle. When created, it can be awaited immediately, but it won't resolve until its execute() method is called and completes. The execute() method runs the action's callback and returns a promise that resolves when that callback finishes. This separation between creation and execution gives schedulers fine-grained control over when work actually happens.

CallbackAction

CallbackAction is an extension of ScheduledAction which represents work that is issued to a subscriber that was created using the subscribe() method. This is the most common action as a new instance will hypothetically be created every time an observable emits a value, and is largely what we're interested in coordinating when we use custom schedulers as it represents a distinct side effect.

CleanupAction

CleanupAction is an extension of ScheduledAction that represents work that should be executed when a subject is disposed of. While there's no difference in how it's implemented, it's useful to have a distinct type for this as it represents a different type of work. When scheduling, we typically handle these cleanup actions differently than other actions.

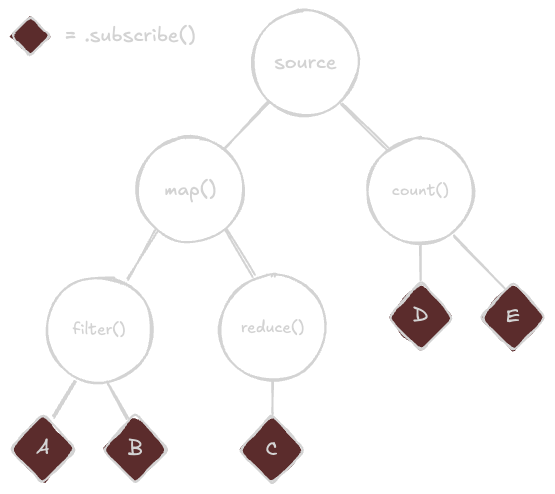

Composing Observables

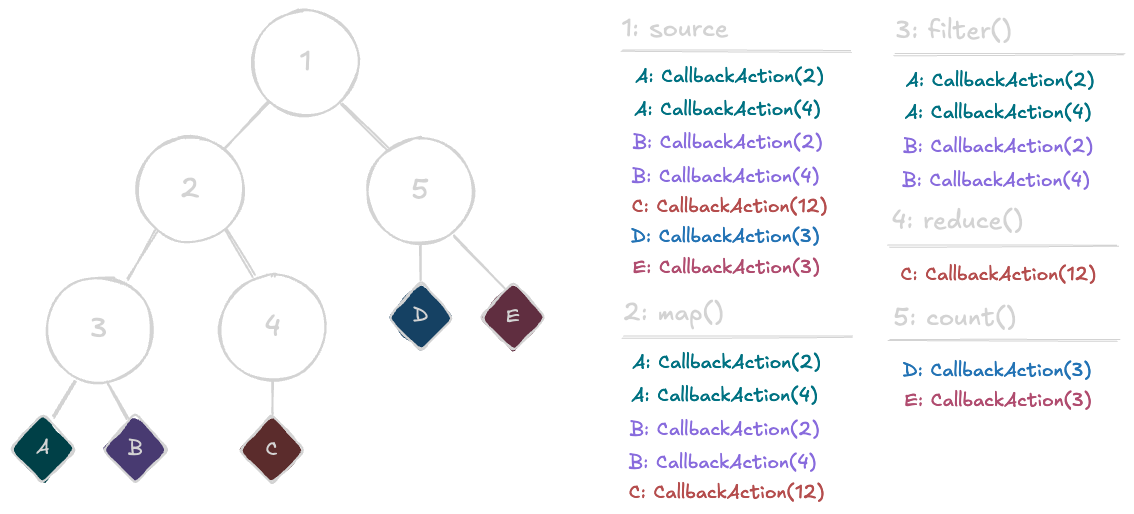

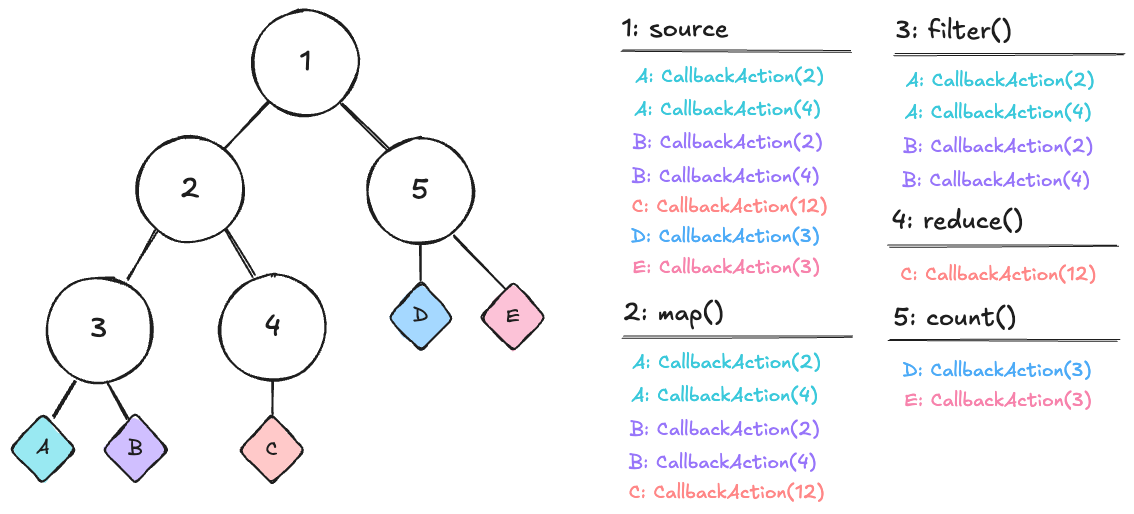

When transforming the data of an observable, the transformations naturally fan out to be a tree-like structure with the root node being the source observable, the branches being the individual pipe() operations, and the leafs being the subscribers. This is because operator functions most typically return an observable observing a different observable. They yield values independent of its source, but typically yields them as a reaction to its source emitting a value.

A representation of this in code might look like:

const source = AsyncObservable.from([1, 2, 3]);

// left side of the tree

const mapped$ = source.pipe(map((value) => value * 2));

const filtered$ = mapped$.pipe(filter((value) => value < 5));

const subA = filtered$.subscribe(console.log);

const subB = filtered$.subscribe(console.log);

const reduced$ = mapped$.pipe(reduce((acc, value) => acc + value, 0));

const subC = reduced$.subscribe(console.log);

// right side of the tree

const counted$ = reduced$.pipe(count());

const subD = counted$.subscribe(console.log);

const subE = counted$.subscribe(console.log);What we have is a composition of observables. This means that each observable in the chain is responsible for transforming the data it receives from its parent and passing it down to its children. Each observable is independent, with its own lifecycle and subscription management, but they work together to form a cohesive data flow. When a value is emitted from the source, it travels down through the tree, with each transformation potentially creating new values, filtering out values, or aggregating values before they eventually reach the subscribers at the leafs of the tree.

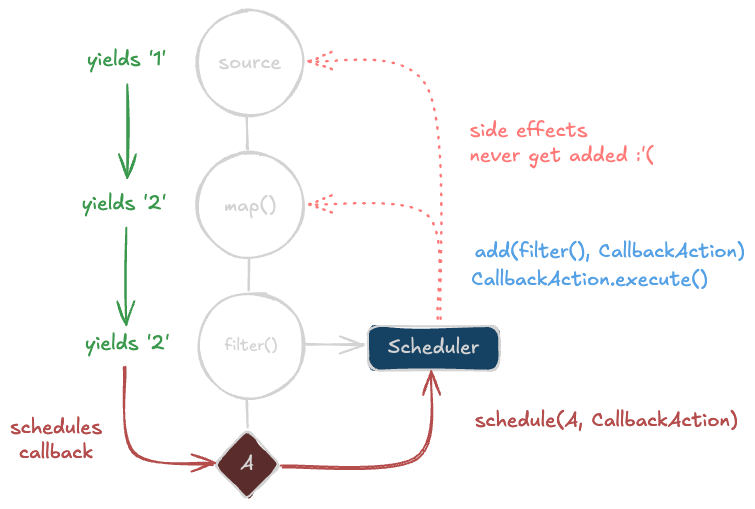

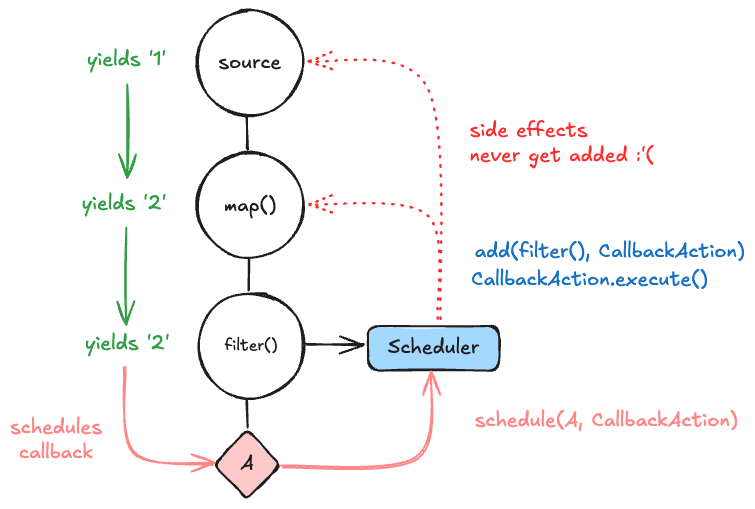

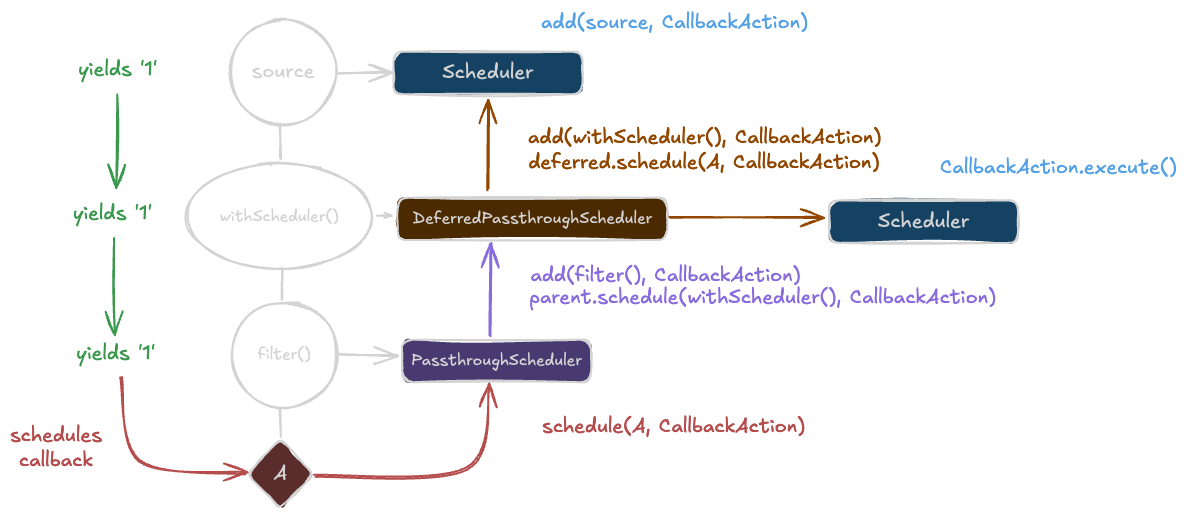

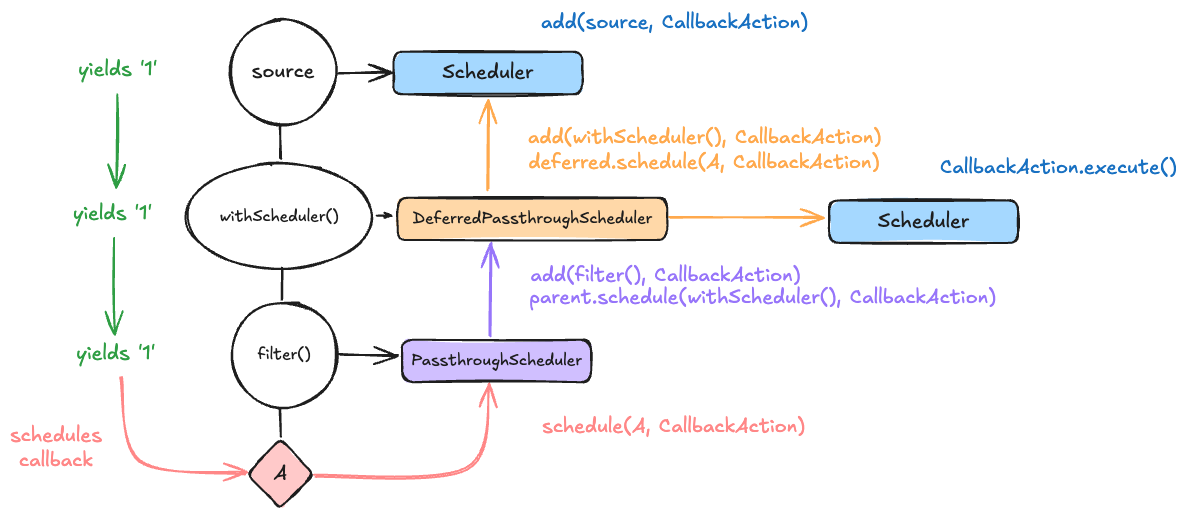

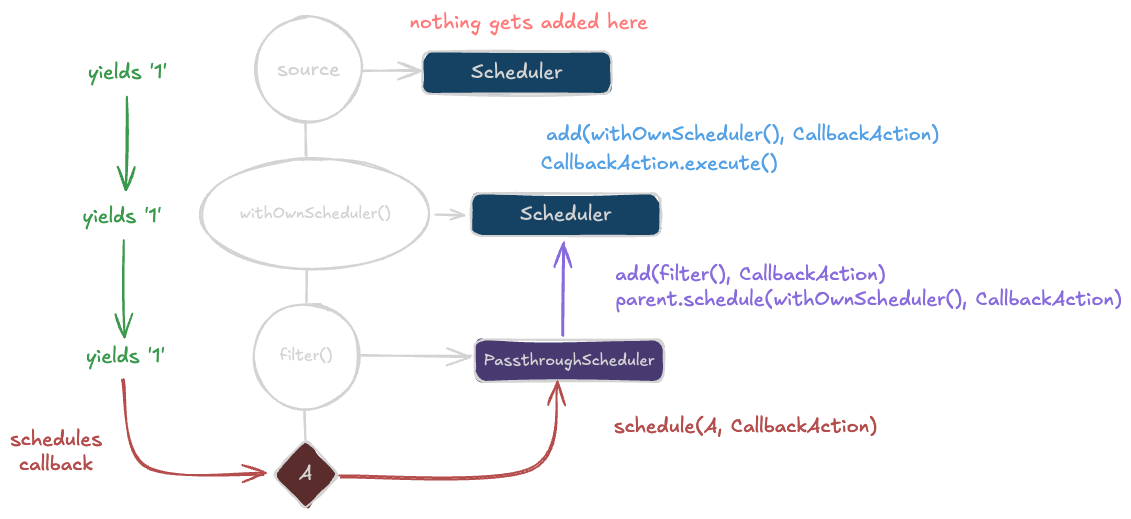

But there's an issue. While the propagation of values from the source observable to the subscribers is straightforward, the propagation of side effects back to the source observable is not. Even though the callback happens many branches away from the source, it still happened as a result of the source observable emitting a value, so it's still considered a side effect.

To illustrate this with just a subset of the tree:

So how do we fix this?

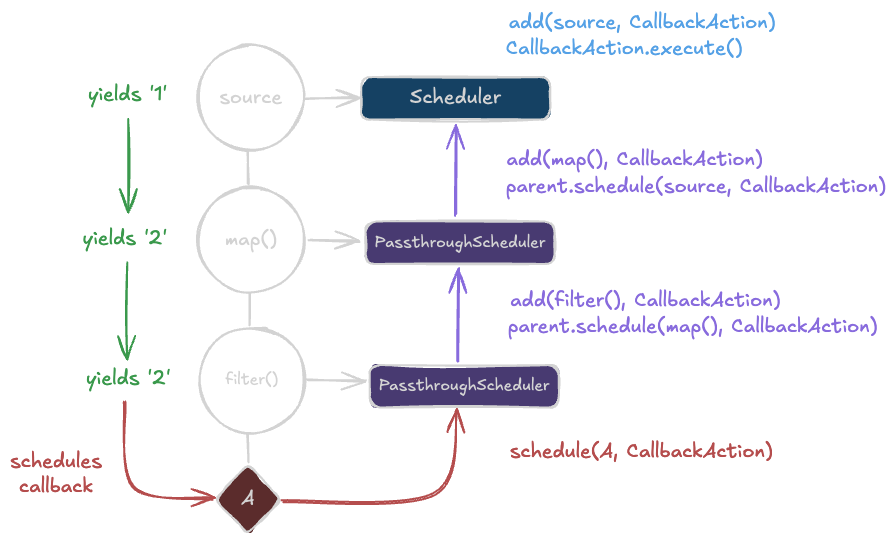

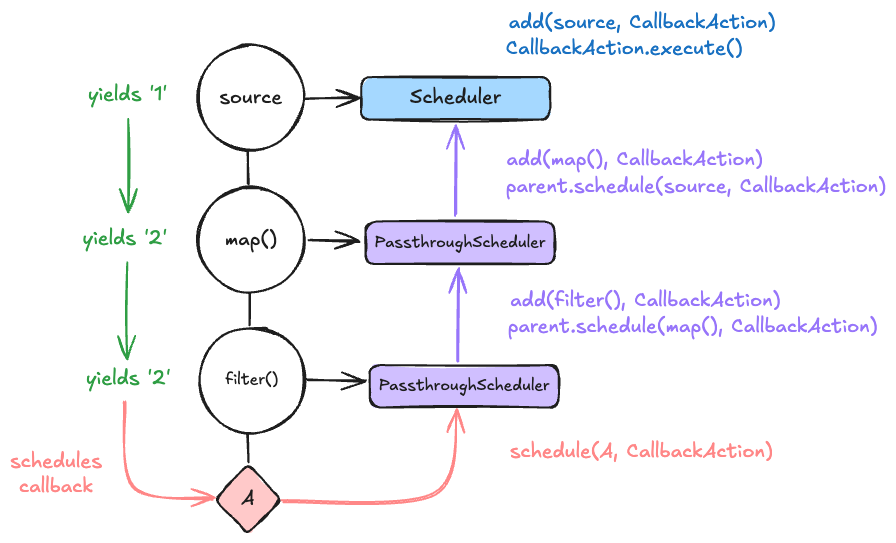

The PassthroughScheduler

Eventkit internally uses a PassthroughScheduler that will also "pass" any work assigned "through" to a parent scheduler object while also adding it to a different subject that we statically know about (the parent observable). This lets us control how side effects get added across the entire composition.

You may also notice that the PassthroughScheduler forwards the schedule call to the parent. This is intentional as it means that whatever execution dynamic the root scheduler imposes will be applied to the entire composition. (i.e. if we put a QueueScheduler on the root, all callbacks to A, B, C, D, and E will be processed sequentially.)

INFO

The base AsyncObservable class exposes an 'AsyncObservable' property that represents a "sub-class" of the current observable that, when constructed, will initialize with a PassthroughScheduler that will forward all work to the parent or source observable.

i.e. new AsyncObservable initializes with a generic Scheduler, new source.AsyncObservable initializes with a PassthroughScheduler that forwards to source

Creating observables in this way is the standard way of how operators are implemented.

A childs work is a subset of its parents work

If we go back to our original example with the entire composition, simulate the source observable being exhausted, and introspectively look at what work was added to each node, we can see that the work associated with a node naturally only contains the work associated with itself and its children.

What this means in practice is that we can individually wait for the completion of any observable in the graph, and it will only wait for the work that is downstream of it.

If for instance the D and E subscribers take callbacks that take a long time to process, we can wait for the completion of the map() observable and it will only wait for the work associated with A, B, and C and not be blocked by D and E.

// will wait for A, B, and C to complete

await mapped$.drain();

// will wait for A, B, C, D, and E to complete

await source.drain();

// will wait for D and E to complete

await counted$.drain();Scheduler operators

Eventkit provides a couple of different operators that let you further control scheduling.

withScheduler

The withScheduler operator imposes a scheduler that threads the side effects to a parent scheduler (like PassthroughScheduler), but instead of having the parent scheduler handle the execution, it lets a different scheduler handle the execution entirely. It does this by imposing a DeferredPassthroughScheduler that works similarly to PassthroughScheduler, but instead of calling parent.schedule() when it encounters a side effect, it calls deferred.schedule() instead.

For instance, say we wanted to process values sequentially for a set of subscribers, but we still wanted to track the execution of the side effects upstream.

import { AsyncObservable, QueueScheduler, withScheduler } from "@eventkit/base";

const source = AsyncObservable.from([1, 2, 3]);

const subA = source.subscribe(console.log);

const scheduler = new QueueScheduler();

const queued$ = source.pipe(withScheduler(scheduler));

const subB = queued$.subscribe(console.log);

const subC = queued$.subscribe(console.log);

// will wait for A, B, and C to complete, but B and C will be processed sequentially

await source.drain();

// will wait for B and C to complete, which will process sequentially

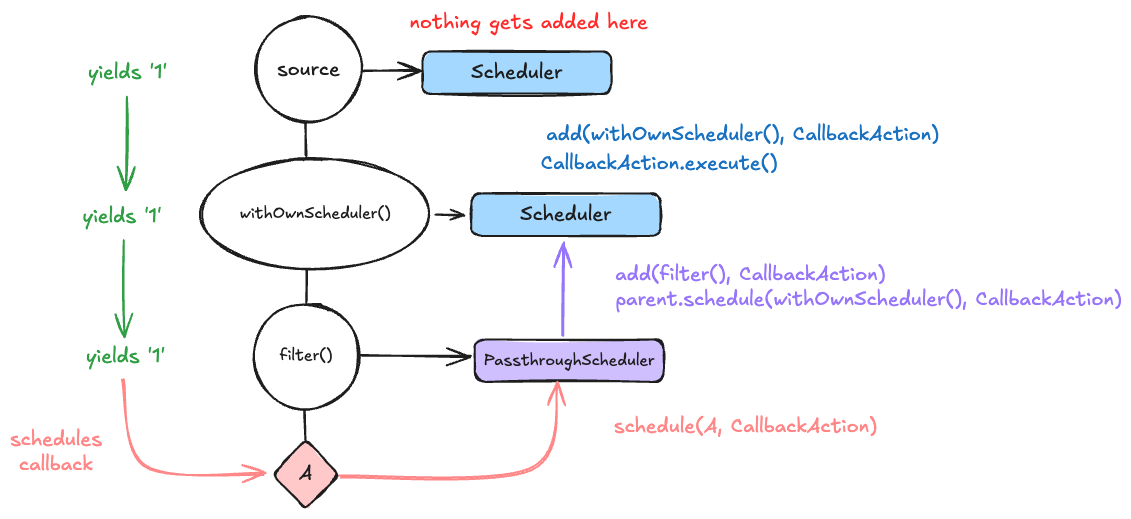

await queued$.drain();withOwnScheduler

The withOwnScheduler operator sidesteps the notion of a passthrough scheduler entirely and imposes the provided scheduler on the returned observable. This could be useful if you want to decouple side effects from the source observable entirely.

import { AsyncObservable, Scheduler, withOwnScheduler } from "@eventkit/base";

const source = AsyncObservable.from([1, 2, 3]);

const subA = source.subscribe(console.log);

const decoupled$ = source.pipe(withOwnScheduler(new Scheduler()));

const subB = decoupled$.subscribe(console.log);

const subC = decoupled$.subscribe(console.log);

// will only wait for A to complete

await source.drain();

// will only wait for B and C to complete

await decoupled$.drain();INFO

This only decouples the side effects from the source observable, not the values. If the source observable finishes or is cancelled, the child observables will also finish.

Example: Queue Scheduler

Say you wanted to process values from an observable in a sequential order. You would do so by imposing a QueueScheduler on the observable.

import { AsyncObservable, QueueScheduler, withScheduler } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield* [1, 2, 3];

});

async function handleValue(value: number) {

await delay(1000 - value * 100);

console.log(value);

}

// example 1: no queue scheduler

await myObservable.subscribe(handleValue);

// (since higher value numbers take less time to process)

// output:

// 3

// 2

// 1

// example 2: queue scheduler

const scheduler = new QueueScheduler();

await myObservable.pipe(withScheduler(scheduler)).subscribe(handleValue);

// (values are processed in order, so it doesn't matter how long each callback takes)

// output:

// 1

// 2

// 3