Async Processing

A big component of eventkit's design is in how it organizes and processes work. While existing implementations of the Observable Pattern in JavaScript largely assert that, by default, all work will happen synchronously in the main loop when an observable is called, eventkit takes the approach of treating all work as work that can be deferred to a later time.

Losing that flexibility might seem like a big regression at first, but baking that assumption in as a primitive actually enables a lot more in terms of concurrency and observability which would otherwise be hard to replicate. Since eventkit handles that abstraction by using JavaScript's async/await primitives, it also allows us to still emulate that synchronous behavior in a way that's still fully async and non-blocking.

In reactive programming, you often hear the term "side effects" a lot. While that term often has a lot of different interpretations, in eventkit side effects are any work that is done as a result of a value being yielded by an observable (like the execution of a callback).

INFO

It's worth noting that we use the terms async/await and Promise pretty interchangeably here. What's important to know is that when we bring either of these up, we're talking about the native methodolgy by which JavaScript handles deferred work. (A Promise represents a value that will be available at some point in the future, which can be created using an async function or the Promise constructor, and can block the call stack from continuing until that value is made available using await).

async/await represents completion

The Observable Pattern takes a lot of care to distinguish itself from a standard Promise. The key difference being that a Promise represents a single value that will be available at some point in the future, while an observable represents any number of values that will be available at some point in the future.

That distinction is important because the very mechanism by which data flows through an observable is different than how data flows through a Promise. But even with that in mind, there's two questions that are important to answer that aren't solved by the observable model in itself:

- How do we know when an observable has finished yielding values?

- How do we know when an observer has finished processing those values?

Notice the key operator finished in those two questions. When we talk about the "observability or lifecycle of an observable", we're largely talking about introspectively knowing when those completion events happen. Since we can only finish work once, the async/await model actually makes for a natural way to represent this completion.

While it might seem intuitive to represent this completion by having a special "complete" notification that gets emitted by an observable at the end of execution, that would mean we'd have to augment our definition of an observable to be a "collection of values over time + a completion event". By representing completion using async/await, we can keep the definition of an observable pure, but still have a way to observe completion in a way that works well with the rest of JavaScript.

How work gets collected

Work is representative of anything that needs to be done in the future as a result of interacting with a subject (like an observable or subscriber). We can signify the completion of a subject when all the work associated with it has been completed. Some examples of this include:

- The execution and completion of an observable's generator function

- A callback being executed and finishing when a value is yielded (a side effect)

- A value being pushed to an iterator object (a different kind of side effect)

- Work that happens when an observable has finished (cleanup work)

- Work that happens as a result of an error being thrown (error handling)

The way that this gets tracked is through the implementation of a Scheduler. Each observable/subscriber has a scheduler that is responsible for tracking the work associated with it. By default, all eventkit objects use a default scheduler that handles the async behavior described in this guide, but you can also provide one of the standard schedulers that ship with eventkit, or implement your own to augment the behavior of the scheduler (More on that in the Scheduling section).

One of the implementation details of the default scheduler is that when we add any work to a subscriber (the object returned by .subscribe()), we're adding the work to both the subscriber and the observable it comes from. This means that when we're waiting for an observable to finish, we're also implicitly waiting for all the work associated with the subscriber to finish.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

// The usage of this observable means that we're implictly adding 4 work items:

// - The execution of the generator function

// - The 3 callbacks that will be scheduled to run since we're yielding 3 values

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield* [1, 2, 3];

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(async (value) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log(value);

});

// this will resolve when the 4 work items mentioned above have all finished.

await sub;

// this will resolve when the 4 work items originating from the subscriber

// have all finished. if we added another subscriber, we'd be doubling up

// on the work items and waiting for those to finish as well

await myObservable.drain();Why is this important?

Say you had a stream of events that had a bunch of expensive non-related side effects that happen when an event is yielded. You might want to wait for all of that work to finish before you continue processing.

const expensiveCalculation = myObservable.subscribe(async (event) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log("a:", event);

});

const saveToDatabaseSubscriber = myObservable.subscribe(async (event) => {

await saveToDatabase();

console.log("b:", event);

});

// You can either (1) wait for ALL the work to finish

await myObservable.drain();

// or (2) wait for a specific subscriber to finish

// (this wont wait for expensiveWorkA to finish if it takes longer)

await saveToDatabaseSubscriber;

// (i.e. I want to make sure that my database has updated before I query it)

await queryDatabase();How Streams are different

Streams are a unique kind of AsyncObservable that will indefinitely yield values that are sent to the stream using push() until the stream is cancelled. Internally, it does this by using a generator function that will wait for the next value to be pushed, and then yield it.

Since the stream's generator function will never complete on its own (and by extension any stream Subscriber's wont complete either), there will always be one piece of work that is pending (the generator function).

import { Stream } from "@eventkit/base";

const stream = new Stream<number>();

const sub = stream.subscribe(console.log);

await sub;

// if nothing was different, this would NEVER get called

console.log("done");What this means in practice is that we can't observe the side effects of a stream in a meaningful way since those will finish way before the stream is cancelled, but we'll never know since we're perpetually waiting for the stream's generator function to complete.

The implementation of Stream solves this by using an intermediary scheduler (called StreamScheduler) that intentionally ignores the generator function's completion. Instead, it only waits for the work that comes from the stream's Subscriber and any other side effects that may be added.

import { Stream } from "@eventkit/base";

const stream = new Stream<number>();

stream.subscribe(async (value) => {

await delay(1000);

console.log(value);

});

stream.push(1);

await stream.drain();

console.log("done");

// output:

// 1

// doneScheduler

The concept of a scheduler in eventkit is largely what coordinates the tracking and execution of work. All units of work are represented by a promise-like object, and attached to a scheduler subject (which can be an AsyncObservable or Subscriber) through the scheduler. When you call drain() on an observable or await a subscriber, all that's happening is you are asking the scheduler for a promise that resolves when all the work associated with that subject has finished.

Scheduling

More details on how this works and how work is handled can be found in the Scheduling section.

Waiting for completion

Using await Subscriber or Subscriber.then()

You can wait for all the work associated with a subscriber to finish by using await on the subscriber object.

import { Stream } from "@eventkit/base";

const stream = new Stream<number>();

const sub = stream.subscribe(async (value) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log("a:", value);

});

sub.push(1);

await sub;

console.log("done first");

sub.push(2);

await sub;

console.log("done second");

// output:

// a: 1

// done first

// a: 2

// done secondWe can await the subscriber multiple times because the subscriber isn't a real JavaScript Promise object. Instead it's a custom "Thennable", which means it has a custom then method which will be called every time the subscriber is in an await statement. When you use an await statement, it's asking the scheduler for the promise that represents the completion of its work at that point in time, which means that if you await the same subscriber multiple times, you'll get a new promise each time.

Since await is just syntactic sugar for .then(), you can also wait for a subscriber to finish by calling .then() on the subscriber object to register a callback.

const sub = stream.subscribe(async (value) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log("a:", value);

});

sub.then(() => console.log("done"));Returning a subscriber from an async function

A common gotcha with using subscribers is that if you return it from an async function, the value you get back is the same promise that comes from awaiting the subscriber. This can cause some hard-to-debug issues if you're not expecting it. For instance:

async function addSub() {

const sub = stream.subscribe(async (value) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log("a:", value);

});

return sub;

}

// sub is Promise<void>, not Promise<Subscriber>

const sub = addSub();This is because of how JavaScript promise chaining works. If you return a promise from an async function, awaiting the return value also implicitly awaits the promise (or promise-like object) you returned.

You can circumvent this by wrapping the return value in an object that isn't promise-like:

async function addSub() {

const sub = stream.subscribe(async (value) => {

await doSomeExpensiveWork();

console.log("a:", value);

});

// all suitable options

return () => sub;

return [sub];

return { sub };

}Using AsyncObservable.drain()

Alternatively you can wait for all the subscribers that belong to an observable to finish by awaiting the observable's drain() method.

import { Stream } from "@eventkit/base";

const stream = new Stream<number>();

const a = stream.subscribe((x) => console.log("a:", x));

const b = stream.subscribe((x) => console.log("b:", x));

stream.push(1);

await stream.drain();

console.log("done");

// output:

// a: 1

// b: 1

// doneAdding cleanup work

If you need to do some work when an object has finished, you can add this work by calling the finally() method on either the subscriber or the observable.

import { Stream } from "@eventkit/base";

const stream = new Stream<number>();

const sub = stream.subscribe((value) => {

console.log(value);

});

await sub.finally(() => console.log("done"));

// ... or

await stream.finally(() => console.log("done"));finally will add the callback that's provided to the scheduler and return a promise that resolves whenever that cleanup work has completed (which is at the discretion of the scheduler, but usually happens after all previous work has finished).

Note that when you register a finally callback against an observable (i.e. stream.finally), that cleanup work will only be executed once you drain or cancel the observable (and when all pending subscribers have completed). This isn't the case for a subscriber's finally callback, which will execute whenever the subscriber is disposed of either by the observable's generator finishing or by the subscriber being cancelled.

Also note that using finally will implicitly add the cleanup work to the subject, so awaiting the subject will also wait for the cleanup work to finish.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

});

console.log("before");

myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

myObservable.finally(() => console.log("🧹 cleaning up"));

await myObservable.drain();

console.log("after");

// output:

// before

// 1

// 🧹 cleaning up

// afterWARNING

A common misconception is that finally will wait for all cleanup work to finish before resolving. This is not the case. finally will only wait for the callback provided to finish, which will happen concurrently with the rest of the cleanup work when the subject is disposed of.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

});

myObservable.finally(async () => {

await new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, 1000));

console.log("longer cleanup");

});

await myObservable.finally(() => {

console.log("shorter cleanup");

});

console.log("before drain");

await myObservable.drain();

console.log("done");

// output:

// shorter cleanup

// before drain

// longer cleanup

// doneError handling

Handling errors in eventkit takes on a bit of a unique shape from how errors are handled in plain JavaScript because of the distributed nature of observables. If you think about how errors are thrown in a function or a promise, we can expect that when an error is thrown, it will only be thrown once and will halt the execution of a function. Because a subscriber uses the values yielded by an observable and schedules its own independent execution, each one of those executions can throw an error independently. In other words, multiple errors can happen in the execution of an observable.

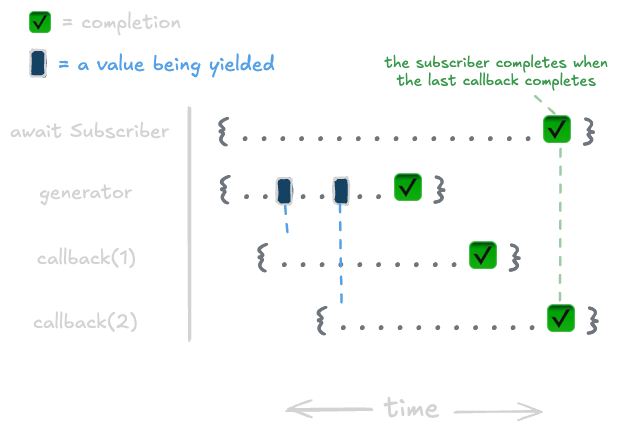

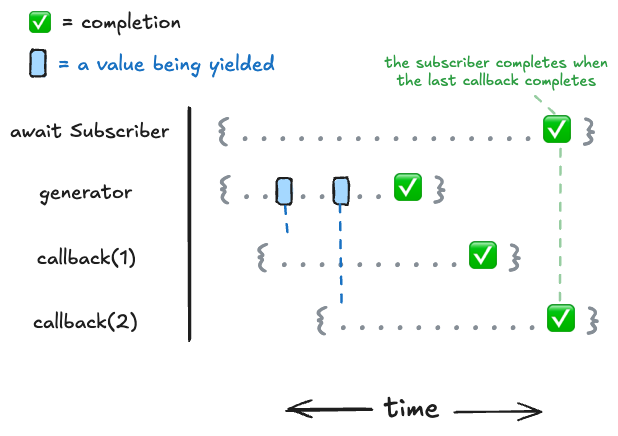

Let's take an example of an observable that doesn't error to give a baseline into how work is handled in eventkit.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield* [1, 2];

});

await myObservable.subscribe(async (value) => {

await delay(1000);

console.log(value);

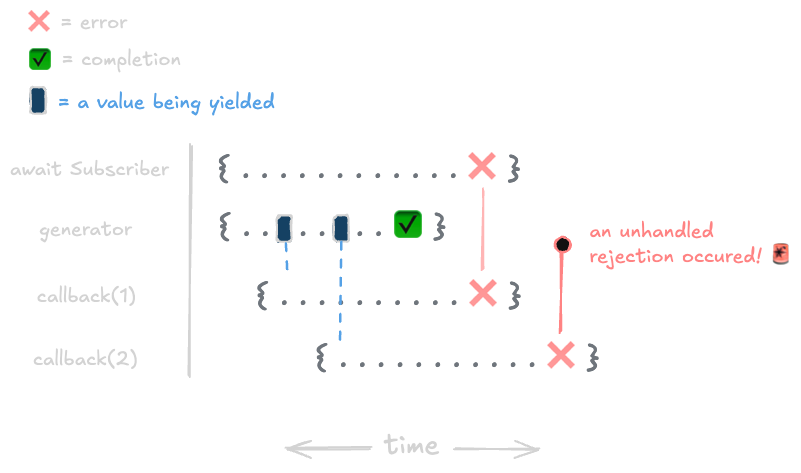

});We can represent the work that occurs in the observable over time like this:

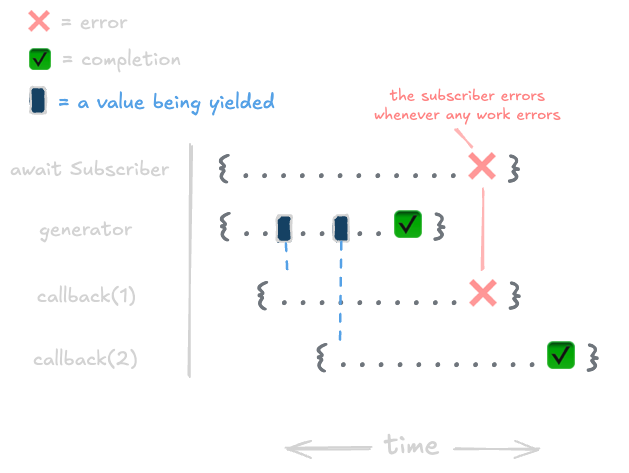

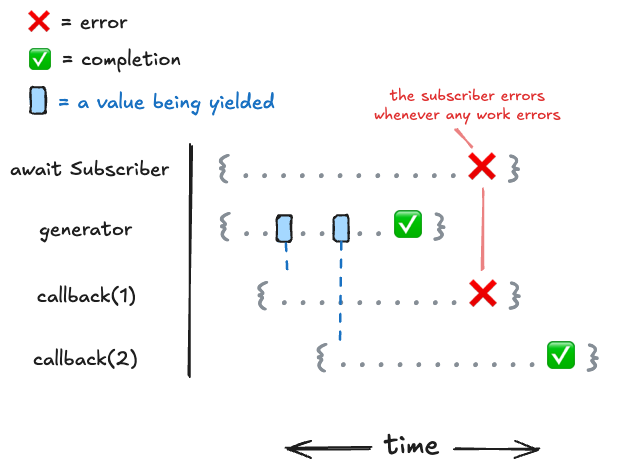

Now let's say that we have some condition where a callback throws an error.

await myObservable.subscribe(async (value) => {

await delay(1000);

if (value === 2) {

throw new Error("oh no");

}

console.log(value);

});We can represent how that error will be propagated through the observable over time like this:

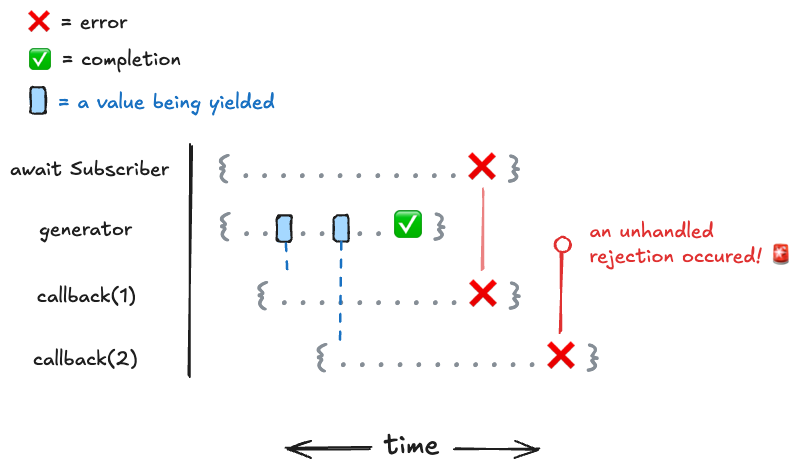

What this demonstrates is that any time an error occurs (which could be in the generator function or in the callback as demonstrated above), the error will immediately be thrown to the promise that called for the work to finish. An important thing to note here is that because the error is thrown in the middle of the work, we've lost the ability to observe the status of the rest of the work (i.e. the completion of callback(2) is no longer tracked). This can be especially problematic if multiple errors get thrown in the same execution:

await myObservable.subscribe(async (value) => {

await delay(1000);

throw new Error("oh no"); // always throw an error

});

Why is this? By default, eventkit objects use this behavior because it's the most intuitive way to handle errors using async/await. If an error occurs somewhere, we want to immediately know about it so that we can handle it appropriately rather than deferring it. While it might seem better to wait for all the work to complete and then collect any errors that occurred, this is problematic because we might either (1) be perpetuating bad application state since we can't take any corrective action against it until after the observable has completed, or (2) might never know about the error at all since observable executions can be indefinite.

As mentioned in the Observable Pattern guide, async/await is prime for representing a single value that will be available at some point in the future (either as a resolved value or rejected error). It's how we represent completion in eventkit, but it's also the mechanism by which we raise errors as soon as they occur. Since we've asserted that multiple errors can occur in the execution of an observable, how do we appropriately handle a collection of errors over time?

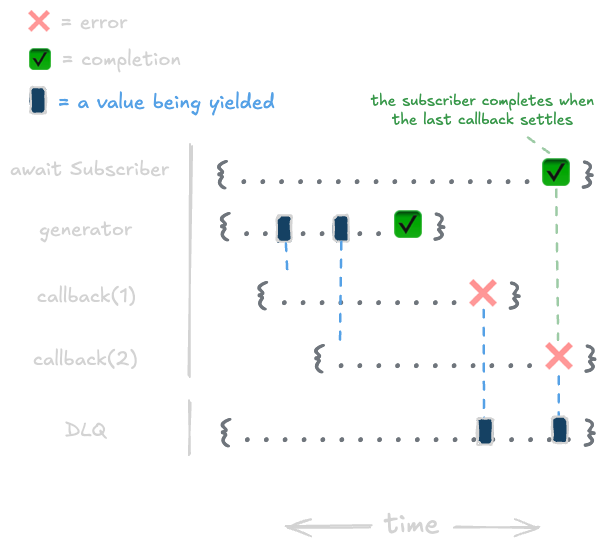

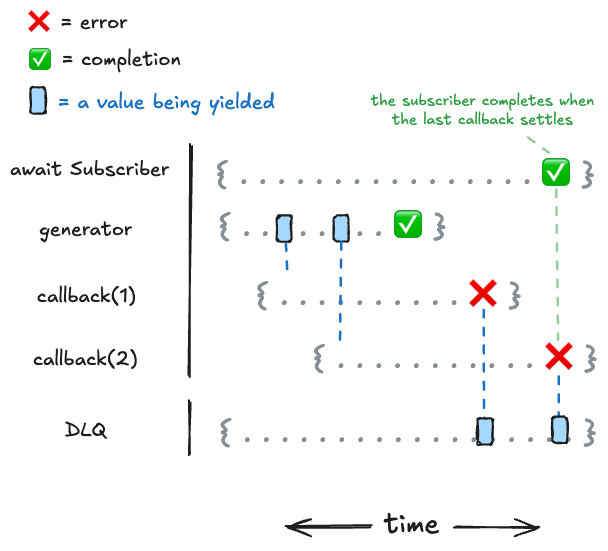

Using the dlq() operator

With the observable pattern, we've established a really neat way to represent values over time. And since we can represent errors as values, we can use the same pattern to represent errors over time.

DLQ stands for "Dead Letter Queue", and is often used in messaging systems to represent a queue of messages that couldn't be delivered. In eventkit, it's used to handle errors that occur in subscriber callbacks by sending them to a different observable.

The dlq() operator takes an observable and returns a new observable that emits the errors that occur in the original observable's subscriber callbacks.

import { AsyncObservable, dlq } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield* [1, 2, 3];

});

const [handledObservable, errors] = myObservable.pipe(dlq());

errors.subscribe(async (error) => {

console.log("sending error to logging service:", error);

await logError(error);

});

handledObservable.subscribe((value) => {

if (value === 2) {

throw new Error("oh no");

}

console.log(value);

});

await myObservable.drain();

// outputs:

// 1

// sending error to logging service: Error: oh no

// 3We can represent how those error values get propagated like this:

WARNING

Note that the dlq() operator will only catch errors that occur in subscriber callbacks. If an error occurs during cleanup or in the generator function, the error will propagate in the same way as mentioned above. Because of this, it's important to recommended that you use try/catch in the generator or cleanup work to handle errors that occur in those areas.

Using the retry() operator

Often times we want to handle callbacks in such a way that we can allow errors to occur, but still propagate them if they continue to occur. This is especially helpful in areas where errors are expected to occur (think network requests, database transactions, dom updates, etc.). The retry() operator is a standard way to handle this by retrying the callback using the specified strategy a certain number of times before eventually re-throwing the error.

import { AsyncObservable, retry } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield* [1, 2, 3];

});

await myObservable.pipe(retry({ limit: 3 })).subscribe((value) => {

if (Math.random() <= 0.5) {

console.log("whoops", value);

throw new Error(`oh no ${value}`);

}

console.log(value);

});

// example output:

// 1

// whoops 2

// whoops 2

// 2

// whoops 3

// whoops 3

// whoops 3

// Error: oh no 3Using try/catch

You can use the native try/catch block in areas where you want to handle errors.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

// in the generator function

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

try {

yield await fetch("...");

} catch (err) {

console.log("error in generator function:", err);

return;

}

});

// in the subscriber callback

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(async (value) => {

try {

await doSomethingWithValue(value);

} catch (err) {

console.log("error in subscriber callback:", err);

}

});

// in the cleanup work

sub.finally(async () => {

try {

await doSomeCleanup();

} catch (err) {

console.log("error in cleanup:", err);

}

});

await sub; // no errors will be thrown hereSince the execution of an observable's generator is stable (it outputs values/errors exactly in the order they're yielded and can be observed in its own definition), we intentionally don't use the same error semantics as we do for subscriber callbacks as mentioned above. What this means is that errors thrown in the generator function will always be thrown immediately and will always cause any subsequent work to be left hanging, regardless if you impose a dlq or retry operator on the observable. Because of this, it's important to use try/catch in the generator function to handle errors if you want to avoid work being left hanging.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

try {

yield await fetch("...");

} catch (err) {

console.log("error in generator function:", err);

return;

}

});

await myObservable.subscribe((value) => console.log("value:", value));

// output:

// error in generator function: Error: oh noHow errors propagate

When calling AsyncObservable.drain() or awaiting a Subscriber, the promise that gets returned is representative of the current work thats being executed. Subsequently awaiting any promises after an error gets thrown won't yield the error rejection since the work that was rejected has already been discarded.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

throw new Error("oh no");

yield 3;

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

// Error: oh no

await myObservable.drain();

// undefined

await myObservable.drain();import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

throw new Error("oh no");

yield 3;

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

// Error: oh no

await sub;

// undefined

await sub;During cleanup

If we define cleanup work either by adding a finally() callback or using a try/finally block in the generator, any errors that occur in the cleanup work will be thrown to the promise that called for the cleanup work.

For instance, if we're waiting for the natural completion of a subscriber and we have cleanup work that throws an error, that error will be thrown to the promise that's awaiting the subscriber.

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

try {

yield 1;

} finally {

throw new Error("oh no");

}

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

// Error: oh no

await sub;import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

sub.finally(() => throw new Error("oh no"));

// Error: oh no

await sub;Or if we do an early cancel of a subscriber, any errors that occur in the cleanup work will be thrown to the promise returned by cancel().

import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

try {

yield 1;

await delay(10000);

} finally {

throw new Error("oh no");

}

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

// Error: oh no

await sub.cancel();import { AsyncObservable } from "@eventkit/base";

const myObservable = new AsyncObservable(async function* () {

yield 1;

await delay(10000);

});

const sub = myObservable.subscribe(console.log);

sub.finally(() => throw new Error("oh no"));

// Error: oh no

await sub.cancel();